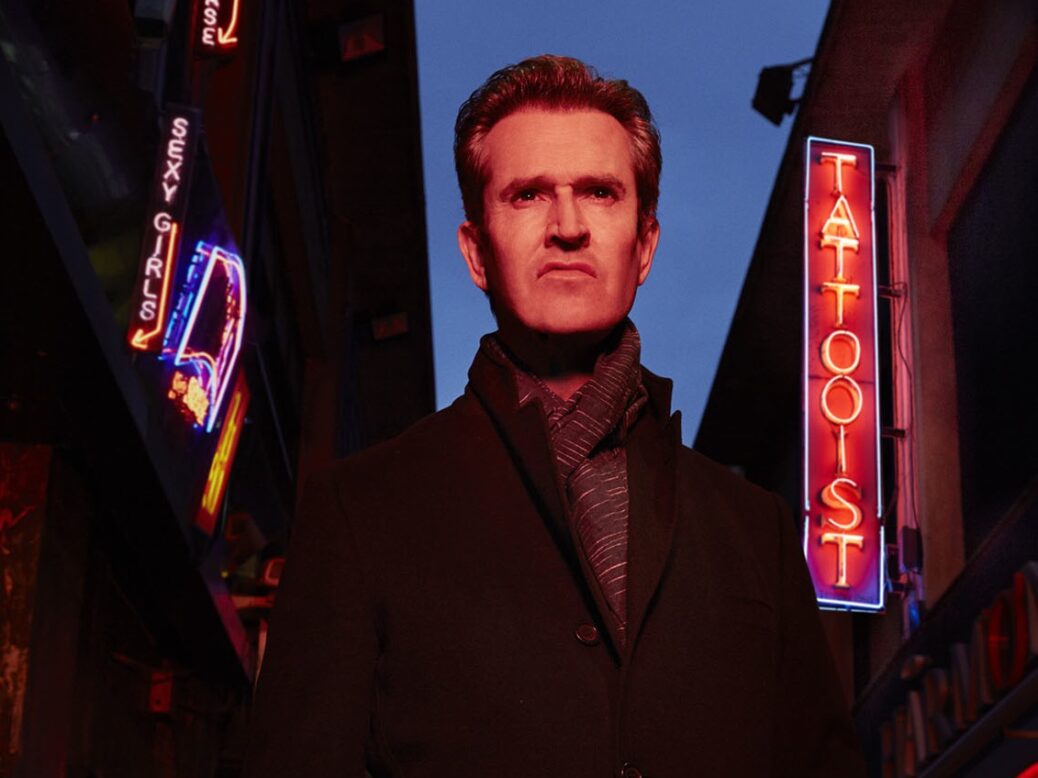

Rupert Everett introduces his Channel 4 documentary, Love for Sale, with an explanation. Prostitution and acting are “the world’s oldest professions,” he says; the only difference between the two being that, while actors “sell their feelings,” prostitutes “grind away at their pussies with much less fuss but with more wear and tear”. In fact, Everett considers himself “the greater whore” and is “frustrated” that despite the “fine line between acting and whoring,” actors are given greater rewards and privileges in this world.

This misogynistic and ignorant introduction sets a tone that persists throughout the first episode.

While the series claims to explore how and why prostitution happens, the reality of servicing strange, often violent men, day in and day out and of being physically used and abused as a means of survival is glossed over. In reality, prostitution is not the world’s oldest profession – it is one of the world’s oldest oppressions.

One of the greatest failures of the first episode is Everett’s unwillingness to acknowledge that which is most evident. The first episode asks “why people sell sex,” but avoids the most obvious answer: demand. “People” (the vast majority of whom are women) sell sex primarily to men. If there were no male demand for paid sex, there would be no prostitution. Another unaddressed truth is that prostitution is not and has never been about female desire or fulfillment. Rather, it exists because of male power and entitlement. We, as a society believe not only that men have the right to access women’s bodies, but that buying sex doesn’t simply fulfill a desire, but a need. Everett himself believes that in order to abolish prostitution, we would need to “re-wire” men’s brains.

This grim outlook on men’s nature, wherein we assume men “need” sex with women who don’t desire them shows little concern for how that supposed “hard-wired” “need” impacts women.

When writer and exited prostitute, Rachel Moran, who authored a powerful memoir detailing her seven years as a prostitute in Dublin, speaks with Everett, he is dismissive. When she tells him that “unwanted sex, even if you are paid for it, is damaging” and that society need not include prostitution, Everett doesn’t listen, lecturing her as though she is delusional. “There is no way of changing this fundamental thing,” he says.

But Everett’s notion of a “safer, cleaner, more comforting” industry is the real delusion. It exists nowhere in history or in our current world. What he is defending is institutionalised oppression.

“Half of me don’t want,” an escort named “Juliana” who sends most of her earnings back to her family in Brazil, tells Everett, “and half of me needs.” The camera stares at Juliana’s breasts as Everett explains to her that she “lives like a movie star”. He speaks on her behalf, so we’ll never know if she agrees.

“I never liked this work and never wanted to do it,” a male prostitute working in Tel Aviv tells Everett. The young man is an illegal immigrant from Jordan who doesn’t have the ID card needed in order for him to move to Israel. He sells sex because he has no other choice. The man is Muslim and says: “if suicide was permitted, I would have done it.”

A high-end male escort named “Bruno” tells Everett that he lost eight friends to suicide in the last 18 months and that the work leaves you “in very dark places” psychologically. Yet Everett concludes that the only harm of prostitution is that those in the industry are made into “social outcasts.” When Everett discusses his friend Lychee, a transwoman who was murdered while prostituting, he fails to acknowledge that the violence came, not from abstract ideas such as social stigma, but from individuals – men, specifically. Often the very men who pay for sex.

Despite what happened to Lychee, Everett is unwilling to stop romanticising the industry, saying about Paris’s Bois de Boulogne, where many transwomen work as prostitutes and where Lychee was murdered: “I adore this place, the notion of have sex outside in the trees – to me, this is a place of great romance and mystery…” “…And danger of course,” he adds, as an afterthought. What Everett calls “eccentric” and “human” is violent and destructive to others and for that reason, people’s “eccentricities” are of less interest to me than the lives of those impacted and destroyed by what Everett sees as “funny games”.

Blaming abstract ideas like “social stigma” and religion functions as a means to avoid addressing a more unpleasant reality – that prostitution is physically, mentally, and emotionally damaging and that most people enter into prostitution because they are marginalised and have no alternative. “It isn’t the stigma we need to eradicate,” Moran tells Everett, “it’s prostitution itself.”

“We aren’t doing it because we love it,” a British woman, working the streets to pay for her drug addiction tells him, “it’s a case of survival.” Does Everett think she would feel differently if “stigma” weren’t a factor?

On a whiteboard at an escort agency he visits, there are notes about certain clients (Everett calls them “the naughty boys”). Next to the name “Johnny12” is the word “rough.” Everett jokes: “Johnny12 sounds my type.” As though the violence suffered by women in prostitution is nothing more than a kinky, sexy little joke.

Everett claims he wants to “get behind stereotypes” that say prostituted women are either “immoral slags” or “powerless victims” but it feels as though he simply wants to replace one stereotype with another – that of the “happy hooker.”

Everett visits Amsterdam, where prostitution is legal, in an effort to show how “empowering” it is when prostitution happens “out in the open”. But in this supposedly “safe” atmosphere, women continue to be murdered and abused in the legal shop windows. A woman he speaks to there spends her days “screening” the gangs of drunken men who walk by her window, trying to guess which ones might rip her off, beat her, or worse. Is this what “empowerment” looks like?

Everett wants to sell a notion of prostitution as glamorous, sexually liberating, and economically empowering, but reality gets in the way. “A teacher can nearly double her weekly take-home income with just a good day’s work with this agency,” Everett proclaims. As though living in a world wherein a teacher must resort to selling sex on the side in order to survive is a great social achievement.

Everett claims to have set out to uncover the “truth” about prostitution in Love for Sale, but it’s clear he – like so many others in this world – is unwilling to see the truth, lest his fantasies be destroyed. The title of the documentary speaks to this – in prostitution, it isn’t “love” that is for sale, but rather power, sold by those who have none.

Meghan Murphy is a writer and journalist from Vancouver, Canada. Her website is Feminist Current. Meghan advocates for a model of law known as the Nordic model, which decriminalises prostitutes and criminalises the johns. You can follow her on Twitter @meghanemurphy.